Navigation and time keeping are two fascinating subjects that, at some point, joined together and became accomplices. Astronomy was the first significant ally of navigators, because since 1620, with the help of astrolabes and other gadgets, the height of the North Star allowed sailors to calculate the North-South position (latitude) of their boat within an acceptable range. However, its East-West position (longitude) was a completely different challenge.

At the beginning it did not seem to be very important. Vessels of explorers and traders plied the waters between America and Europe without problems. Curiously, the length of voyages to the same destination would fluctuate for periods of several weeks because they could not determine the exact position of the vessel.

It takes our planet 24 hours to complete a 360- degree revolution on its axis, which means that the East- West position of a boat can be calculated in terms of time. And that is why the search for a method of determining longitude remained in the hands of timekeepers.

Being able to calculate the difference in time between the site where the vessel is located and the time at a point of reference (that we now know as meridian zero or Greenwich time) is what allows navigators to establish their longitude, but the precision of the position goes hand in hand with the exactness with which the time interval can be measured.

Precision was the problem, because after weeks or months at sea the reliability of timepieces was affected by variations in temperature, humidity and the instability of the vessel, on which, naturally, a clock that functions with a pendulum is completely useless.

The problem became more and more critical by the moment. The international struggle to dominate the seas was relentless and there was also the matter of pirates. The straw that broke the camel’s back, however, occurred in 1707 when an English fleet, under the command of Admiral Clowdisley Shovel, was grounded near the islands of Sicily in fog that was so thick that visibility was only 20 centimeters (12 inches).

The disaster, in which more than 2,000 men lost their lives, could have been avoided if the admiral would have known the exact longitude.

It was then that the British parliament offered a prize of 20,000 pounds (the equivalent of something like three million dollars in today’s currency) to anyone who offered a “practical solution” for determining longitude at sea. If the solution was in a timepiece, it would have to be one that performed precisely within a range of two seconds per day, and would maintain this level of accuracy during a voyage of two years at sea.

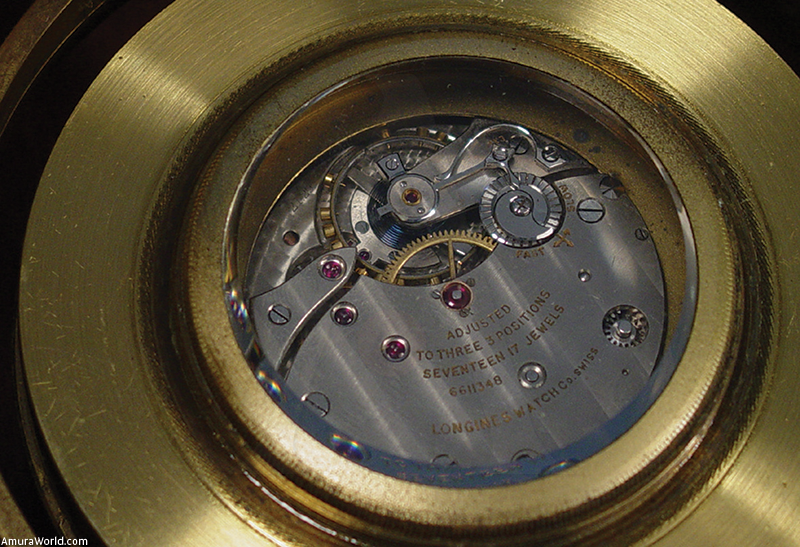

John Harrison, a carpenter, approached the problem from a different angle and he was successful where the best watchmakers failed. He developed a series of clocks that began with the H1 which, because of its dimensions, was not considered very “practical.” He improved on it until he eventually won the prize with the H4 (only six inches in diameter) when it returned successfully from a three-year voyage exploring the South Seas, under the command of Captain James Cook. Harrison’s invention, in addition to converting the English fleet into the most powerful of its time, prompted the invention of timepiece mechanisms that reduce friction, mitigate the effects of changes in temperature and other sophisticated advances. It thus helped to develop the art of watch making, speeding it towards horizons of micromechanical feats that no one could previously have imagined, and that we are rediscovering for you in this section.

Text: Tonatiuh ± Photo: Tonatiuh.