There are currently two exhibitions of one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century, Louise Bourgeois, one in Boston and the other in various European and US cities.

The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston is showing the simple entitled “Bourgeois in Boston”, that brings together works of public and private collections of the city. It has been open to the public from last year and will run through March 2008.

London’s Tate Modem in collaboration with the Pompidou Center in Paris has organized a retro- spective. Having been presented at the Tate, it will continue traveling from the Pompidou (spring 2008), to the Guggenheim in New York (summer 2008), the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art (fall 2008) and the Hirshorn Museum & Sculpture Garden in Washington (spring 2009).

Both exhibitions display a mosaic of her work, bringing together all the traditional and non-tra- ditional supports with which she worked during the 70 years of her artistic production. Painting and engravings from her early career, her first sculptures in wood (which Bourgeois grouped under the title “Characters”) and at the end of the 1950s, she began to sculpt in bronze.

Both exhibitions also unite the artist’s sculp- tural work produced between 1960 and 1980 in bronze and marble, as well as pieces made from resins, latex and rubber. There is also a collection of her later work, which concentrate and stress her obsessions in large-scale works and y sculptures in textiles that she began producing in the 1990s.

On seeing her works, the spectator must keep in mind that Louise Bourgeois’s art is highly auto- biographical and is based on the reconstruction of the trauma left by her first years of infancy and youth. Bom in Paris in 1911 into the bosom of a family that worked on the restoration of old tapes- tries. From a child, she was used to repairing dam- age and working with discarded objects. In 1938, she married art historian Robert Goldwater and they emigrated to New York, where she lived from then on.

Bourgeois works with delicate status of the soul, centered on the business or pain, abandon- ment, betrayal, loneliness, anxiety, trauma, as well as the existential cost of individuation, subjectivi- ty and growth. Abjection is a theoretical platform that allows us an approach to the sculpture she produced from the 1960s to the 1980s.

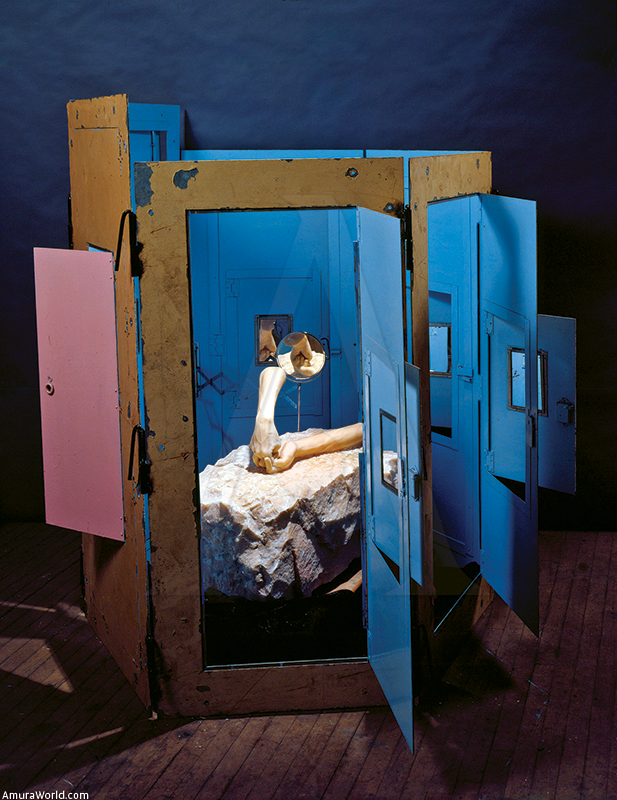

Monolithic works denounce the trembling identity that upholds the subject and its child, and always a fragile, sexual identity. In her works of this time, Bourgeois turns the body into a reitera- tive mass of part-organs. Fury is a feeling that models these forms of anthropomorphic reminis- cences, formations that in their paroxysm lead the human state to a mineral, inorganic state. Returning from the landscape to the undifferenti- ated sludge from which life emerges, there is a constant parceled perception of the body that is compulsively retaken over and over again. Bourgeois’ work is abject because it makes any cat- egory or state of order impossible. Her shapes cre- ate confusions between the kingdoms of man and woman, animal and human, organic and inorganic. Genital protrusions evoke ocular and tactile for- mations while mammary prominence bears wit- ness that the law of the phallus is false and has been overturned. This can be seen in her keynote work of 1974, The Destruction of the Father. Parricide and anthropophagie, brothers!

Louise’s work is very different once time has silenced the rage. The last decades of her life have woven a spider’s web of the inappreciable loss of the melancholic object. Her work as a tribute to the memory and forgiveness are grouped with the name “Cells”.

On the one hand, the cell is an architectural form of reclusion and isolation with comments about her own house and family and on the other; it highlights the biological term “cell”, as the min- imal unit of life.

In all ways, cells are fed from the memory as an inventory of discarded objects and minimal units that time has passed by. This is when age catches up with our sculptor, who then starts to work with textiles and soft materials she has collected over the years. Her sculptures retake the form of the body; this time not as a part-object but as complete mutilated and prosthetic forms. A state of grace, of forgiveness, weaves these bodies in the Frankenstein sense.

Louise knows the ambivalence of the god Janus, who governs life; she knows that strength lies in the capacity to undermine. She knows that we have all been marked by trauma and so as we run along life’s slop, we lose some parts, some members and some illusions. She knows this and she also knows that we will eventually need some kind of prosthesis and supplement to be able to survive our own invalidity.

Text: Anarela Vargas ± Photo: Cortesía The Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston, TATE Modern