Egypt, a millenary tradition

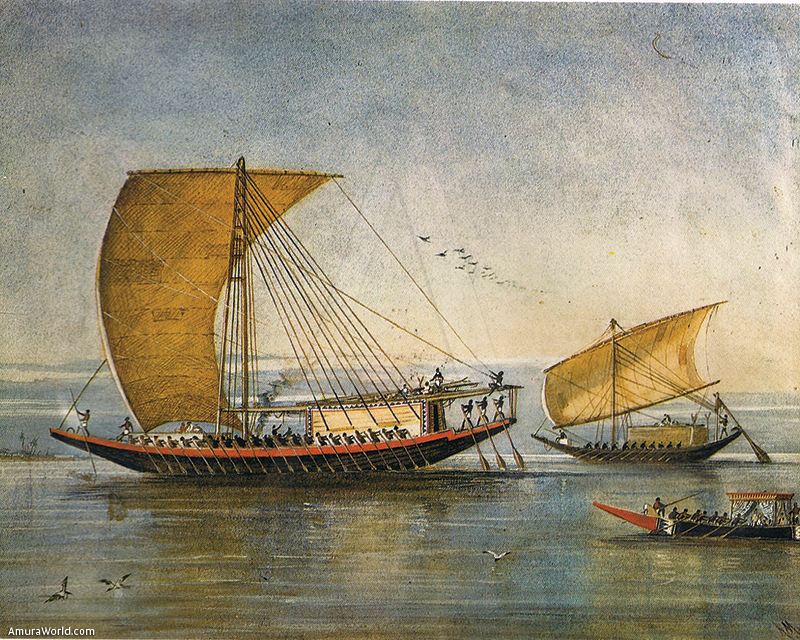

The slow flowing Nile was almost ideal for transportation though occasional storms which might endanger shipping or the lack of wind held it up. From earliest times Egyptians built boats for transportation, fishing and enjoyment. Their importance in everyday life is reflected in the role they played in mythology and religion.

Little is left of actual boats. Remains of Old Kingdom boats were found at Tarkhan and Abydos, and King Khufu’s ship is well known and demonstrates best how ships were built during that period.

The first dynasty boats found at Abydos were about 25 meters long, two to three meters wide and about sixty centimeters deep, seating 30 rowers. They had narrowing sterns and prows and there is evidence that they were painted. They do not seem to have been models but actual boats built of wood too much decayed to analyze, some suspect that it was cedar, others deny this. Thick planks were lashed together by rope fed through mortises. The seams between them were caulked with reeds. The boats did not have any internal framing and were twisted when they were uncovered.

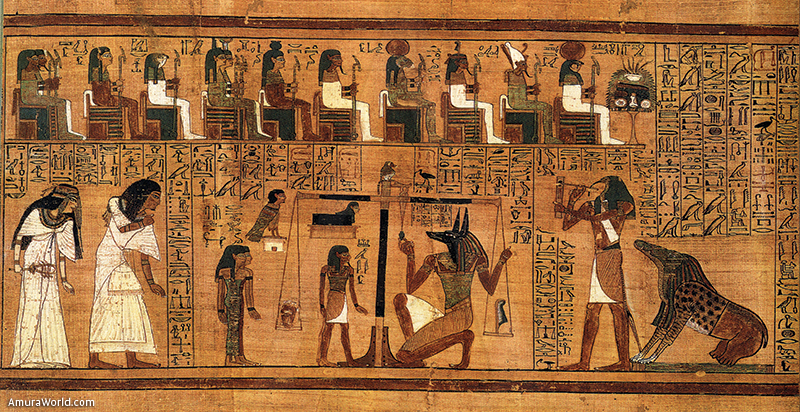

Egypt abounds with pictures and models of boats and ships. The walls of temples and tombs at Deir el Bahri and Medinet Habu are covered with them, but very little is known, about how New Kingdom ships were actually put together.

Sometimes we know what the boats looked like without knowing what they were called, at others we have their names but do not really have much of a clue what they looked like. On the coffin of the 4th dynasty prince Minkhaf, which was found in a mastaba in the eastern Giza cemetery, there are inscriptions of offerings and among them a list of boats.

The state involvement

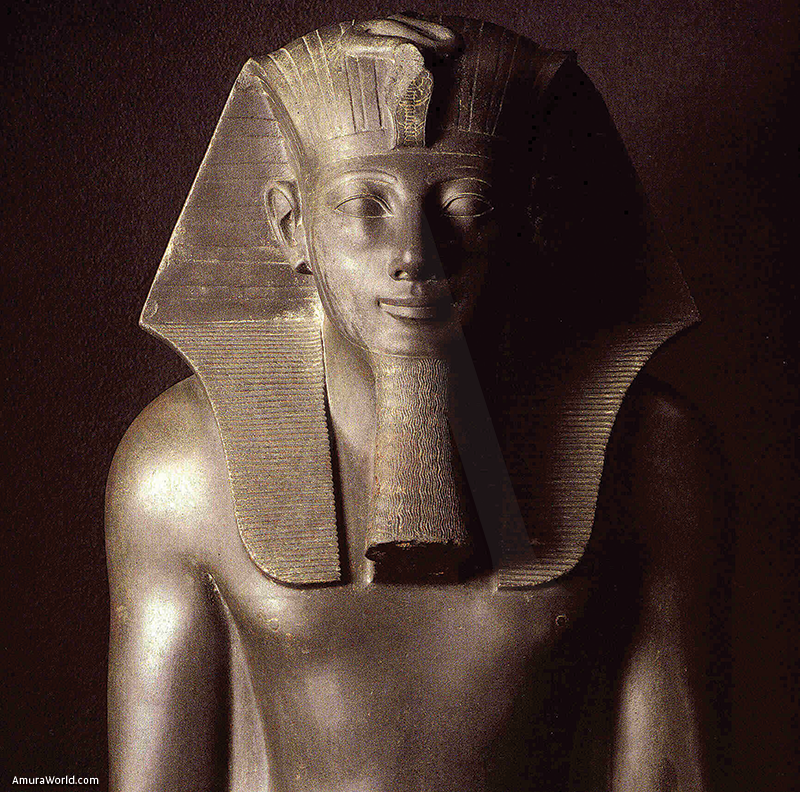

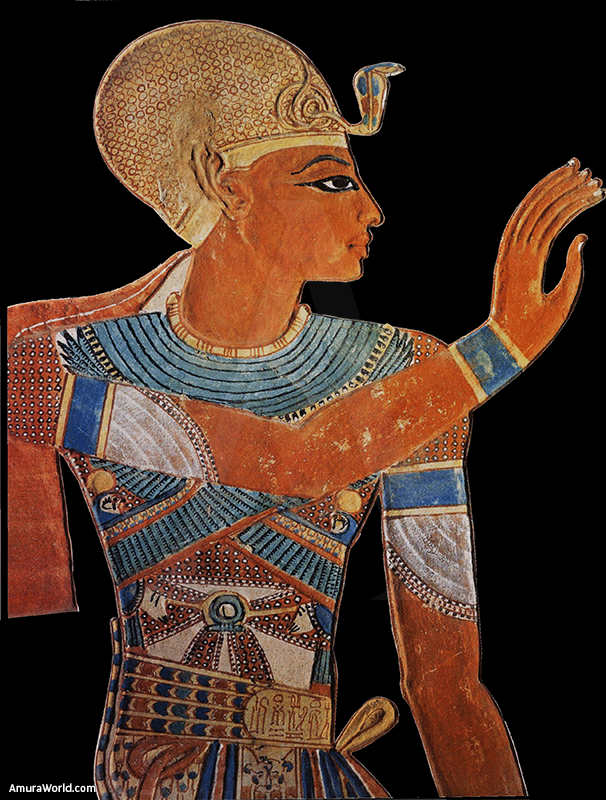

A number of pharaohs saw the need for a strong navy, i.e. Snefru who according to the Palermo Stone built 100-cubit ships of meru wood and 60 sixteen-barges before hacking up the land of the Negro, bringing of 7,000 prisoners, and 200,000 large and small cattle, Thutmose III, the architect of the empire in Asia, Necho II struggling with the Babylonians and Ramses III, who had to contend with theSea Peoples. Ramses wrote a ‘report’ to Amen

“I built you ships, freight ships, arched ships with rigging, plying the Big Green (the sea). I manned them with archers, captains and innumerable sailors, to bring the goods of the Land of Tyre and the foreign countries at the end of the world to your storage rooms at Thebes the Victorious”.

The royal fleet was supervised by the Chief of the Royal Ships, an important administrative rather than military position, which under the 26th dynasty seems to have included the responsibility for the taxation of merchandise transported on the Nile.

Under Thutmose III the butler Nebamen and under Amenhotep II another butler, Suemniut, were given the office; and in a later era of economical and political growth, the Saite Period, the Overseer of the Scribes of the Magistrates Tjaenhebu, and, under Ahmose II, Hekaemsaf and Psammetik-mery-Ptah filled the post. A like title, Chief of the Ships of the Lord of the two Lands, was bestowed upon one Paakhraef.

Temple fleets were similarly organized: The priests of Amen appointed a Chief of the ships of Amen, the servants of Ptah a Chief of the Ships of the House of Ptah.

>

Egyptian seagoing ships were inferior to those used by other peoples, despite remarkable feats achieved, among them the expeditions along the eastern coast of Africa during the reign of Hatshepsut at the beginning of the 15th century BCE and the crossing of the Indian Ocean with seventy metre long ships in the times of Ramses III 300 years later. From the 20th dynasty onwards the Egyptians began to copy ships used by their rivals.

Many trade and exploration ventures were initiated by the administration, such as the voyages to Punt under Hatshepsut and the circumnavigation of Africa by Phoenician sailors under Necho.

Private ownership of ships existed at least during the First Intermediate Period, documented by biographical inscriptions. The weakness of the state and its consequent inability to build ships needed for the transportation of people and goods stimulated private enterprise.

During the Late Period, Greeks and Phoenicians spread along the Mediterranean coast, building colonies. The Ionians and Carians settled in the Delta and their centre of Naukratis became an important port and was encouraged by a number of pharaohs.

As there was very little wood available, the first vessels were made of bundled papyrus reeds. Simple rafts in the beginning, they grew into sizable ‘ships’ and were, as Thor Heyerdahl proved with his ocean crossing, seaworthy–given luck. They had a sickle shaped hull and often masts and sometimes deck houses.

Small papyrus rafts served the population throughout much of Egypt’s history, for as long as the raw material was readily available. They were cheap to make and did not require great expertise to build. Papyrus died out in Egypt and was reintroduced in the 20th century.

Transportation of heavy loads, international trade and war required stronger ships than could be built from papyrus. These wooden vessels were similar in form to the old reed boats, had a flat bottom and a square stern. As they were without a keel onto which it could be stepped, the mast was often bipod, fastened to the gunwale. Later, under the influence of Byblos, with which they were in close contact, the Egyptians adopted a single central mast, which sometimes was topped with a bronze finial to which the ropes were tied.

Instead of fitting rowlocks on the gunwale to keep the oars in place, rope was used to serve as fulcrum. Smaller boats were paddled.

Ships were constructed in ship-building yards (wxr.t), first mentioned in the Old Kingdom. During the New Kingdom the main ship yard was at Memphis. Specialized carpenters were charged with building the ships. A thirty metre long transportation barge took seventeen days to build. The techniques do not seem to have changed over time. Herodotus’ description of the construction of a ship could have been written centuries earlier:

“Their boats with which they carry cargoes are made of the thorny acacia, of which the form is very like that of the Kyrenian lotos, and that which exudes from it is gum. From this tree they cut pieces of wood about two cubits in length and arrange them like bricks, fastening the boat together by running a great number of long bolts through the two-cubits pieces; and when they have thus fastened the boat together, they lay cross-pieces over the top, using no ribs for the sides; and within they caulk the seams with papyrus. They make one steering-oar for it, which is passed through the bottom of the boat; and they have a mast of acacia and sails of papyrus. These boats cannot sail up the river unless there be a very fresh wind blowing, but are towed from the shore: from this acacia tree they cut planks 3 feet long, which they put together like courses of brick, building up the hull as follows: they joined these three foot lengths together with long close set dowels; when they have built up the hull in this fashion they stretch cross beams over them. They use no ribs, and they caulk the seams from the inside, using papyrus”.

Herodotus, Histories II, Project Gutenberg

Sailing the ships

During the Old Kingdom, ships were steered with two large unsupported oars held by helmsmen in both hands. Later the oars were connected to tillers Even with this improvement steering was hard work. Amenhotep II, a powerful man according to experts who examined his mummy, was described thus.

“His arms were strong and didn’t get tired holding the oar and steering in the stern of the king’s ship, heading a crew of 200 sailors. When the ship stopped after these men had traversed half an atur (about 5 km) they were left without breath; their limbs were weak, they choked. But His Majesty’s strength didn’t fail him steering with an oar twenty cubits long. When he dropped anchor and tied up the ship with a cable, he had traversed three atur steering the ship without resting during the preparations. The hearts of the people were glad seeing his achievements”.

Herodotus, Histories II, 96

In ancient Egypt sails were always rectangular. During the Old Kingdom only the top of the sail was tied to a spar, while the bottom was tied to the bulwarks. Later the sail was fastened between a top and bottom spar. In Akhenaten’s time the advanced brailed sail with small ropes on its edges for trussing came into use, making the furling of the sail easier.

There is archaeological and other evidence that Egyptians adopted many practices of other seafaring nations, such as the Phoenicians and Greeks. In the Late Period Egypt came to depend to a high degree on foreign ships and sailors.

Canals

While the Mediterranean region was easily accessible to Egyptian maritime traders, Eastern Africa was less so.Under Senusret III (1850 BCE) and a number of other pharaohs, the last being Ptolemy II, a canal was being dug and re-dug connecting the Nile to the Bitter Lakes, falling into disrepair during times of trouble.

When no canal was available ships had to be built so they could be dismantled, carried overland through Wadi Hammamat to the Red Sea and reassembled. During the times when these ships were not in use, they were apparently taken apart and stored: in the Wadi Gawasis man-made caves were found which served for storage of timbers, cordage, and other ship’s stores.

The Nile cataracts were obstacles that had to be dealt with. A canal cut through rock enabled navigation beyond the first cataract, and a slipway near the fortress of Mirgissa at the second cataract has been found by archaeologists.

Dams

Dams were built too, sometimes with military or commercial aims in mind, at others probably serving for flood protection or irrigation. Herodotus claims that Menes built a dyke diverting the Nile in order to protect Memphis from inundations. The Sadd el-Kafara in Wadi Garawi, the oldest known dam in the world, collapsed not long after its erection in the early Old Kingdom. Another dam was constructed at Semna probably during the reign of Amenemhet III (1841-1796 BCE) and was in use until the times of Amenemhet V, as the unusually high readings of the river level - 8 meters above normal - seem to bear out. It was apparently constructed in order to facilitate navigation. The dam of Senusret II in the Fayum was built to control the level of Lake Moeris

Harbors

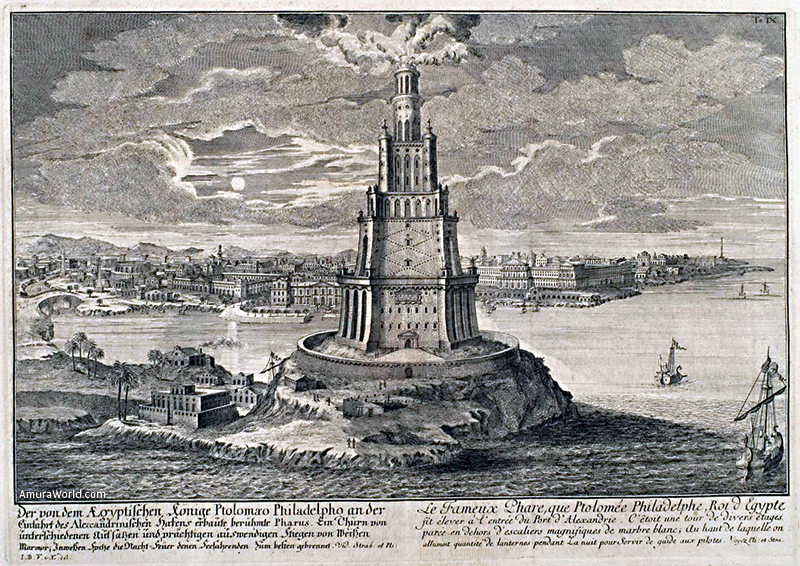

The Pharos lighthouse of Alexandria, perhaps not the first Egyptian lighthouse, Alexandria harbor though no records of any earlier ones have been found, was built under Ptolemy Soter from about 290 BCE till 270 at the entrance to what was to become one of the most important ports of the Mediterranean. Its height of more than 100 meters made it visible at distances of about fifty kilometers. During day time a mirror was used to reflect the sun, at night a fire was lit.

The island of Pharos was later connected to the mainland by the Heptastadium an artificial isthmus which afforded better protection for the Port of Pharos, later the East Harbor.

Harbors and quays were built along the Nile and the Mediterranean and Red Sea coasts [8]. Especially important were well constructed quays in places where heavy loads were shipped, near Qasr el Sagha on the shore of Lake of Moeris for instance. From the quarry at Widan el Faras blocks of basalt were transported to the quay on a road with flagstone pavement. As the height of the Nile differed greatly between the various seasons, at times more than one pier was constructed to serve the same site, thus at Luxor, the low water landing site has two stairs leading to a small platform, five by two and a half meters big, while the high water pier was much more massive, having to serve for the unloading of heavy wares, which were preferably shipped during the inundation season.

In order to get to the Red Sea or pass the Nile cataracts, the Egyptians established slipways for the transportation of their river and sea craft overland. The ships were constructed in such a way, that the could be taken apart and reassembled with relative ease, but at times they were loaded whole on sledges or wagons and dragged to the launching site. Most of these slipways were probably just leveled stretches of dirt road baked stone hard by the sun, but some of them were reinforced with mud bricks, slabs of stone or wooden logs. The length of these slipways could be considerable. At Mirgissa, where the second cataract had to be overcome, the strategically important “boat way” was more than a kilometer long und built on an infrastructure of timber and mud brick.

“... in the land from which they were removed there still remained down to my time the winches with which their ships were drawn up and the ruins of their houses”.

Herodotus, Histories: Euterpe 2.154.1

Text: Museo del Cairo ± Photo: KSC / ARGENBERG /GIBNA KEBIRA / MICHEL KURTZ / KAIRO INFO / wkm / CARLOS SB / SODICA / Academic / Jorge de andes / NUSKCA / ayacata / BP / ISUS